Another year. Another set of decisions made. Another set of decisions analysed. This will be the eleventh time I write such a blog post, just as I did on the 1st of January 2022, 1st of January 2021, 1st of January 2020, 1st of January 2019, 1st of January 2018, 1st of January 2017, 1st of January 2016, 1st of January 2015, 1st of January 2014 and 1st of January 2013. The eagle eyed reader might notice that, having made it through an entire decade of getting this annual post published on the 1st of January, here I am publishing this one on the 10th. A failure, one might think. A breakdown in discipline. A loss of control. The beginning of a slippery slope.

Or, perhaps, a rebalancing of priorities.

I’ve spent the last decade living a life of becoming. When I first started this rigorous process of tracking and evaluating my decisions, I was 27 years old and looking to build a very specific kind of life. A life based on a set of values I’d developed that year, and which I would evolve over time. A life that involved hopefully, one day, a family. A life that included professional success, through a company I would build. Success that would one day culminate in building rockets that go to space.

As I sat down on the morning of the 1st of January 2023, aged 38, next to my third baby, born just a few days earlier, the world, and my life, looked very different. With three children, any idea of control was nothing more than a delusion. As anyone with 3 or more children will know, I am at all times in the middle of a Brownian Motion (mostly metaphorically, although when it comes to the two older boys, often literally too). There is no solving this as a puzzle. Only a probabilistic model can be applied, coupled with constant never-ending inputs and course correction.

As I sat down on the morning of the 1st of January 2023, aged 38, next to my third baby, born just a few days earlier, the world, and my life, looked very different. With three children, any idea of control was nothing more than a delusion. As anyone with 3 or more children will know, I am at all times in the middle of a Brownian Motion (mostly metaphorically, although when it comes to the two older boys, often literally too). There is no solving this as a puzzle. Only a probabilistic model can be applied, coupled with constant never-ending inputs and course correction.

It was clear that my life had shifted – from one that was strictly structured, carefully planned, and efficiently executed in the direction of my goals, to one of just being in the moment, making a relentless stream of decisions based on a system of values, and being grateful for each day. It’s not that I care less about making good decisions. It’s that making those decisions on the fly, based on consolidated learning and experience, otherwise known as gut instinct, is how almost all of my life now works.

It’s taken me time to get comfortable with the concept of a life of being. I spent my entire childhood being taught that life was for becoming. Get the scholarship to Eton. Get into Cambridge. Start a company. It was always achieving the next step that would count as success. I’ve done enough reading now to realise how false that approach is. As any Stoic will tell us (can’t go wrong with Marcus Aurelius), what matters is not what we achieve, but the person we are as we go about achieving it. As any spiritual thinker will tell us (can’t go wrong with Eckhart Tolle), that achievement won’t bring us lasting happiness, only living in the moment will.

And so moving forward I will still analyse my decisions, but I’ll do it because I believe that doing that is vital to keep me on track to be the person I want to be. The outcomes and achievements should still come – a combination of effort, good decisions, and luck should over time add up to them. But living the journey will be what matters.

So what lessons do I have from my good and bad decisions in 2021. A reminder of the process. I pick out my most major decisions, typically 1-3 per month, and carefully evaluate them before making them, taking feedback from other people, and writing out the possible scenarios that might play out. I then keep that document (now a digital template but I still prefer the original handwritten approach and may go back to that), and review it only at the end of the following year. So the decisions I’ve just reviewed were all made in 2021, between 12 and 24 months ago.

The first theme is about thinking, doing and the trust battery:

In all aspects of life, we will always interact with other human beings, and we will often need to rely on them. Sometimes this will be an employee you hire. Sometimes it will be a family member. My first, and biggest lesson, is that to rely on someone, they need to be able to both think, and do. Either one of these without the other leads to a very bad place. Talk must lead to decisions, and in a startup, decisions need to be made quickly, on the fly, and there are many of them. And those decisions need to be executed to a full effective conclusion. Over the course of 2021 I relied on several doers that didn’t think at the appropriate level for their responsibility, and several thinkers that didn’t do at the appropriate level for their responsibility. The dichotomy is so obvious in hindsight, and yet the scenarios were so different that there was no obvious pattern at the time.

There are several corollary lessons that have come from this. The first is the importance of the trust battery. Tobias Lutke recently taked about it with Shane Parrish. I’ve always believed in the concept of the trust battery, and how it can be built up and depleted. Tobi talks about making the same mistake that I’ve made – listening to many people’s suggestion that the best thing for a CEO to do was “hire great people and get out of their way”. A simplistic statement, typically made by people who have not been CEOs or effective executives, which sounds like it makes sense and is therefore is easily adopted as a principle. It is impossible to be certain of someone’s ability to think, or someone’s ability to do, when you first meet them. It’s impossible to be certain of this even after whatever set of interviews you can create, and reference calls which you have. Those have their place in making a decision. But it takes specific direct experiences to understand people’s actual capabilities, and that means that the trust battery starts at zero, and needs to be actively built up. From now on if there is someone new in my life on whom I am relying, our joint focus will be taking that trust battery up from zero, with the relationship changing at each level, and the level of visibility, reporting, collaboration evolving, and with it being categorically clear that increasing that trust batter is as much of an expectation as their other responsibilities.

The second order corollary is that this means that self-awareness, coachability, adaptability, respect and trust in their manager, a focus on commercial outcomes, and relentless ownership and execution, all of these are total expectations. Without each of these, there is no way that the trust battery can be built up, which means that there is no point in even starting. A gap in any of these is an immediate deal breaker.

Ultimately to live a life of being, if I want to have the level of responsibility which I have, I need to surround myself by people I can trust, and who are effective at what they do. Someone fully owning something with zero involvement from me is the perfect outcome. Someone ineffectively owning something is the worst outcome, as it creates more and more debt that then needs repayment. In the middle of those two ends of the spectrum are: me trying to manage something myself, e.g. a department, and me searching for a replacement owner, the latter clearly being better than the former.

The second theme is trusting your gut. Or, differently phrased, if there’s a doubt, there’s no doubt. This one is an oldie but goodie in my decision making learnings.

Analysing these decisions I was once again reminded that if something doesn’t feel right, there is no way to force it to be right. The factors which play into any scenario, any situation, any relationship, are far too complex, and they almost always cannot be unpicked and put back together again. If a relationship is starting off with demands, requirements and ultimatums, it’s not going to get better later. And there’s nothing wrong with that. It just means the fit is wrong and the only next step is to move on.

A few corollaries come from this. The first is to fight the internal bias of pot commitment. The same one that makes you finish a book you’re not enjoying. Even if after months of searching, and a big decision and announcement, you realise something isn’t right, then take the hit, walk away, start again. Easy to write, very hard to do in practice. Our minds play tricks on all of us, telling us that maybe things will get better, maybe we can fix them. A decade of data should be enough to put that one to bed.

The second corollary is one of my favourites. An internal promotion is far lower risk than an external hire, because you know exactly where you stand. That doesn’t mean that everyone will succeed in every role, the Peter Principle is pretty clear about that. But the level of risk and uncertainty with an internal candidate is an order of magnitude lower than an external one, because you already know that it feels right in their current role. And that means that it’s an absolutely vital responsibility of any leader to identify everyone with potential and invest hard in growing them on a multi-year and hopefully multi-decade horizon.

Another lesson within this theme is not to do things because others tell you that you need to. The others don’t know you, don’t know your situation, don’t know your business, don’t know your market. But you do, from first principles. Don’t get me wrong, not everything has to be worked out from first principles, that’ll take far too long. A framework might be useful, if applied and adapted carefully. But “this is how it should be done” is not a good route to go down. Many “much smarter” people will regularly tell you how things should be done. If it doesn’t feel right, don’t ignore that feeling.

The third theme is the inverse of the second. When there’s no doubt, there should probably be a doubt. Helpful, I know.

Sometimes (ok let’s be honest, according to my decision analysis posts, often) people blind me and I’m absolutely certain that they are exactly what I’m looking for. My coach describes them as “brilliant”. They shine so bright, they’re so talented, all of your logical decision making is switched off and you just want to be in their presence. Of course brilliance has quite little correlation with their ability to think and do. So a big lesson for me continues to be, all these years later, to build systems to ensure that I don’t get blinded by brilliant people when it comes to me making decisions.

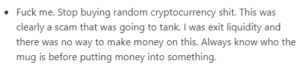

This theme isn’t just about decisions relating to other people. It’s about my own personal decision making as well. 2021 was quite clearly an insane year. I’m pretty sure that in last year’s blog post I wrote that it made more sense to buy a jpeg of a monkey than buying a house. The picture to the left is my actual note evaluating one of the decisions I made in 2021. It is very clear now, in hindsight, that when the world around you starts to lose the plot, when exuberance takes over, when everything prints money, when loss-making software companies are valued at more than the revenue they will generate in a person’s lifetime, when one hundred thousand people try to buy digital land in a monkey multiverse for $20k each and complain that they weren’t allowed to, it is very very clear that this is not normal. And yet, even with the best decision making analysis, I couldn’t time the exit at the top of the market, I couldn’t stop myself from getting involved with random crypto things, and I couldn’t prevent myself from wasting time and money on it. There are situations where biases and irrational thinking takes over, pretending to be good instincts. You cannot alter your behaviour once you’re in that situation. You can only ride it out, hopefully protected by whichever systems you’ve put in place around you. What you can do is stop yourself from entering that situation, or build systems that help you get out of it quickly and safely. This exact process is one of those systems, and it has helped me humongous over the past decade. But there’s clearly a lot left to do.

This theme isn’t just about decisions relating to other people. It’s about my own personal decision making as well. 2021 was quite clearly an insane year. I’m pretty sure that in last year’s blog post I wrote that it made more sense to buy a jpeg of a monkey than buying a house. The picture to the left is my actual note evaluating one of the decisions I made in 2021. It is very clear now, in hindsight, that when the world around you starts to lose the plot, when exuberance takes over, when everything prints money, when loss-making software companies are valued at more than the revenue they will generate in a person’s lifetime, when one hundred thousand people try to buy digital land in a monkey multiverse for $20k each and complain that they weren’t allowed to, it is very very clear that this is not normal. And yet, even with the best decision making analysis, I couldn’t time the exit at the top of the market, I couldn’t stop myself from getting involved with random crypto things, and I couldn’t prevent myself from wasting time and money on it. There are situations where biases and irrational thinking takes over, pretending to be good instincts. You cannot alter your behaviour once you’re in that situation. You can only ride it out, hopefully protected by whichever systems you’ve put in place around you. What you can do is stop yourself from entering that situation, or build systems that help you get out of it quickly and safely. This exact process is one of those systems, and it has helped me humongous over the past decade. But there’s clearly a lot left to do.

One thing in particular I learned very directly was that burning the candle from both ends, pushing yourself beyond breaking point, and operating at a level of burnout, very clear leads to ending up in a situation where the irrationality takes over, even if everything else around is actually normal. There was a period in 2021 where the business, fundraising, the crazy market, global expansion, and the family all came together in an impossible way, and I pushed myself to that place. Coming out of it took many months and much work with my coach, and felt like coming out of a fog.

Theme four is the bigger the prize, the higher the pressure, the more the need for focus.

If you’re running a VC-backed business, then the commercial outcomes are what matter, and everything else is the foundation on which to achieve it. Of course you will have a company value framework, and a personal value framework, and you will be achieving those outcomes within those values. And you’ll have a company purpose, which you’ll hopefully achieve more and more of as you get larger. But the achievement of commercial outcomes is a non-negotiable goal. The delivery of an increased share price, and a successful return to the investors is what you’ve signed up for.

One of my learnings from 2021 is that as the prize gets bigger, the more people have opinions and concerns, and the higher the level of emotional complexity becomes. When Ometria was just a startup, most people involved would see it as a toy – a toy to work for, a toy to own a piece of. As we raised our Series C at the peak of 2021, and suddenly there were 8 zeros involved, the level of intensity and expectation ballooned, from quite literally everyone around the table. This is predictable human behaviour, and having experienced it once I know that as we continue to grow, and as the prize gets even bigger, my job will require me to do more and more visibility, alignment and expectation management.

To do that I’ll need to free up time, and the first paragraph in this theme provides good guidance for how to do that. The end outcome for a VC-backed company is clear – an exit that is considered a success by everyone involved. That means the investors get a return they’re excited about. That means the team members get roles and a future that they’re excited about. That means that customers continue to be served even better going forward. There are many stakeholders to manage, but there are clear exit scenarios which optimise for all of these. If that kind of exit is the core end outcome, then the focus of my role needs to be on the most valuable aspects of achieving it, even if it’s many years away. Detailed operational work is unlikely to make the top of the list. Multi-year planning, putting the right people in place, ensuring we don’t make bad decisions or trap ourselves, all of these however are right up there. A very different type of CEO role to before.

And last but not least, my favourite theme for today. It’s people who win, and there’s always a way to win.

Many, many times over the course of Ometria’s decade-long existence, advisors have told me that you need a core differentiator, and that it can’t just be “our people are better than everyone else”. Well I call bullshit. Because there are a dozen customer data and experience platforms out there now. And some have much more funding and are in much bigger markets. Do we have features they don’t have? Sure. Do they have features we don’t have? Yep. The fact is, the reason Steve Madden and Brooklinen have chosen us over the dozen US competitors that we’ve got is our people. If you’ve got exceptional people, then that will always differentiate you, irrespective of everything else. That’s how we’ve got to where we’ve got to over the past ten years. And it’s how we’ll go even further over the next ten years.

There are many companies out there with hundreds or thousands of employees, stuck in bureaucracy, stuck with lots of underperformers or quiet quitters. More people is not a mark of success. Better results with a smaller team and lower costs, that’s a mark of success. And with the right people that’s 100% possible. I’ve experienced executives painfully struggling to achieve results with large teams, and other executives achieving everything with just one or two, and barely breaking a sweat themselves. Those individuals who know how to achieve a lot with little, they are golden. Invest in them and watch them flourish.

And the grand finale. In early 2021 there was a period that looked pretty bleak for us as a business. Something that had happened before, and will no doubt happen again. But it was really the lowest of the lows. And at that time I remembered two sayings my mother used to tell me. The first is that life is a zebra, if you’re going along a black stripe, then the next one will be white. And the second is that whenever you find yourself with an unsolvable problem, it definitely has at least three solutions. All I can tell you is that she was 100% right.

Here we are, well into 2023. I hope that it has already brought you joy, peace, centeredness and clarity. I hope that your journey through the rest of this year is aligned with both your values and your goals. I wish you good being. Happy new year.